Purchasing professionals the world over are forever on the hunt for two things: top quality goods and services, and the best deal possible.

But even the savviest, shrewdest bargainer at the negotiation table might struggle to match the scope and value of the breathtaking bargain struck by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803: the Louisiana Purchase.

Understanding the history of this famous land deal, and its continuing impact in both the modern Americas and the world, can provide some intriguing insight into not only the importance of the Louisiana Purchase to the young United States, but its enduring legacy in world commerce and culture.

Jefferson’s Gambit: A Louisiana Purchase Overview

Despite living in an age defined by gains in technology, deeper understanding of economic sciences, and a much more prominent role in the global sociopolitical and financial theaters, today’s average American might still struggle to grasp the truly enormous size, and rock-bottom price, of the Louisiana Purchase.

Size Matters

Covering a staggering 530,000,000 acres (820,000 square miles, or slightly more than 2,144,510 square kilometers), the Louisiana Purchase was completed in 1803 for $15,000,000, the equivalent of around $340 million today based on inflation.

That breaks down to about $0.03 an acre for enough land to cover the entirety of Spain, Italy, Germany, France, and Poland, with enough room left over for most of Greece.

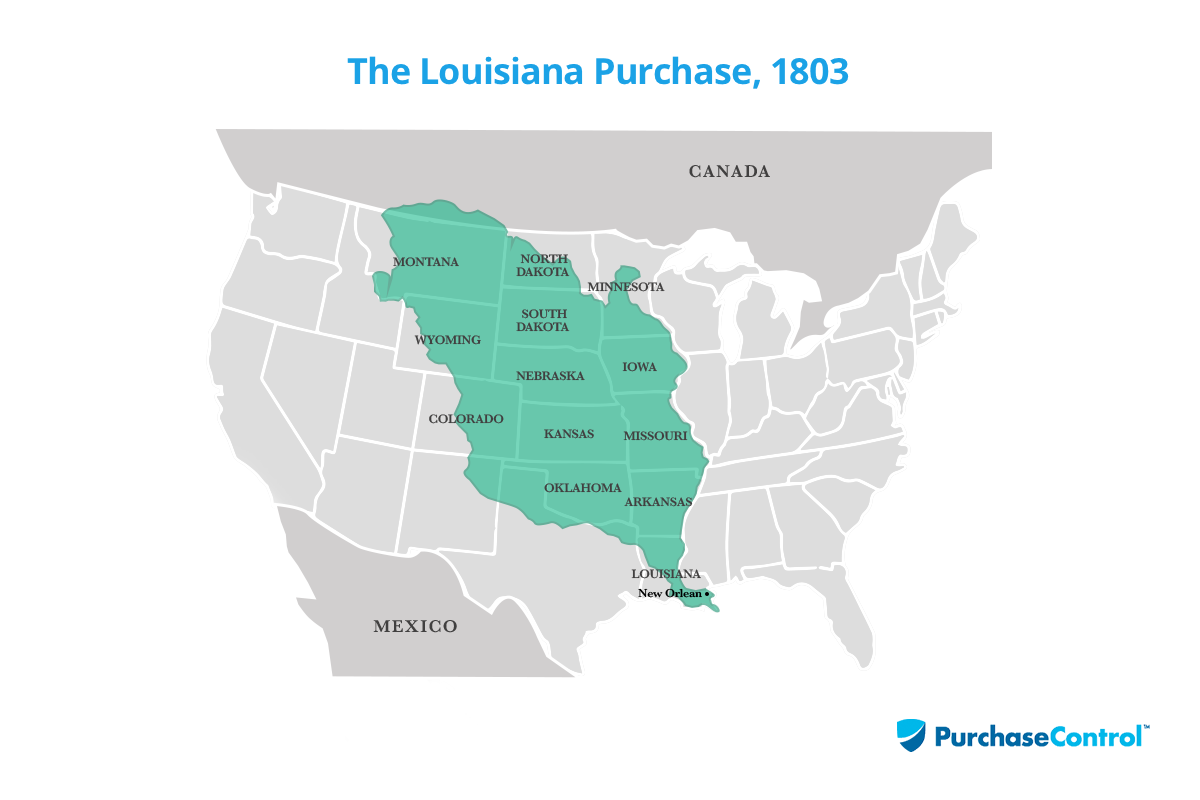

The Purchase itself is bound by the Mississippi River in the East and the Rocky Mountains in the West, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to the border with Canada in the north.

Its final boundaries would not be set until more than a decade after its completion, in 1819, when the purchase of the Floridas from Spain allowed precise boundary lines to be established as follows:

- The northern boundary (established in 1818) was also the U.S.-Canadian border, at the 49° parallel between the Lake of the Woods and the Rocky Mountains.

- The southern boundary traveled a complicated path along the Sabine, Red, and Arkansas rivers from the 32° N parallel to the 42° N parallel, and then west to the Pacific Ocean.

- The Rocky Mountains (known then as the “Stony Mountains”) formed the western boundary.

- The Mississippi River formed the boundary in the east.

The territory contained not only a cornucopia of natural resources and arable land, but enough territory to produce the larger part of thirteen states.

It effectively doubled the size of the United States; the following present-day states were created in their entirety from the Purchase:

- Louisiana

- Missouri

- Arkansas

- Iowa

- North Dakota

- South Dakota

- Nebraska

- Oklahoma

The remaining land was sufficient to provide the majority of the land for five other states as well:

- Colorado

- Kansas

- Montana

- Minnesota

- Wyoming

Pricing the Purchase

It can be hard to pinpoint values for the Louisiana Purchase in today’s dollars, since land valuation varies so wildly in the sprawling and diverse climes of the United States.

Farmland can be valued as cheaply as $3,140 per acre, while urban land values can climb to a staggering $5,000,000 per acre in places like New York City.

Valuing the Purchase today is further complicated by the additional value created by improvements upon it.

However, based on a national average of $12,000 an acre in a 2015 study conducted by economist William D. Larson, we can approximate the value at $6.36 trillion. (530,000,000 x $12,000 = 6,360,000,000,000).

If parsing all those zeros is a struggle, just imagine buying every man, woman, and child in Ireland a house worth €1.3 million. Or, better yet, fire up your purchasing software and see which of your vendors can handle daily orders for a million dollars—for a period of 18,000 years.

Better rent some more warehouse space!

The ambitions of Napoleon made a successful outcome for the States unlikely, but the French ran into serious problems with illness on Hispaniola, financial difficulties across the French empire, and potential war with Britain, creating a “perfect storm” of stressors. Livingston, along with James Monroe, exploited this storm by implying the United States was feeling inclined to strengthen international relations with its former colonial master, Britain.

Before the Deal: Frustration with France

Knowing the scale of the Louisiana Purchase tells us the what of the matter, but does not touch on the how or why.

At the turn of the 19th century, the United States government found itself in an awkward position due to some diplomatic maneuvering by two Colonial-Era titans: Spain and France.

The French had ceded control of the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain in 1762, just as the Seven Years’ War was winding down.

The Spanish were happy to grant the United States duty-free shipping all along the Mississippi, and free temporary storage of goods at New Orleans, in the Treaty of San Lorenzo in 1795.

By 1800, Americans were not only shipping and storing their goods up and down the Mississippi, but settling in the delta and along the river itself.

Complications arose when Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise restored much of France’s lost military prestige and clout.

Napoleon had plans to colonize and exploit the island of Hispaniola (home today to Haiti in the west and the Dominican Republic in the east), and transform the restored territory of Louisiana into a “breadbasket” for the island’s cocoa, indigo, cotton, sugar, and cocoa production—and, by extension, a valuable source of revenue for French empire.

The Spanish king, Charles IV, not only made a verbal arrangements with the French ruler to return the Louisiana Territory to the French, but formally agreed to negotiate the return of Louisiana in exchange for territories in Tuscany via the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800.

Then, to add fuel to the fire, Spain revoked the rights of shipping, passage, and storage at New Orleans for the United States in 1802.

It was clear to both President Jefferson and the U.S. government that the newly belligerent and expansionist French would make for complicated and problematic bedfellows in the growing New World, especially if they controlled access to the port of New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico.

Jefferson dispatched Robert Livingston, the U.S. Minister in Paris, to attempt negotiations with two goals in mind:

- Stop the Spanish from returning Louisiana to the French;

- Purchase New Orleans for a price of up to $9,375,000 from the French if the transfer had already been formalized.

The ambitions of Napoleon made a successful outcome for the States unlikely, but the French ran into serious problems with illness on Hispaniola, financial difficulties across the French empire, and potential war with England, creating a “perfect storm” of stressors.

Livingston, along with James Monroe, exploited this storm by implying the United States was feeling inclined to strengthen international relations with its former colonial master, Great Britain.

A similar land acquisition was the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, in which the United States bought land from Mexico to facilitate railroad construction, further shaping the nation’s borders.

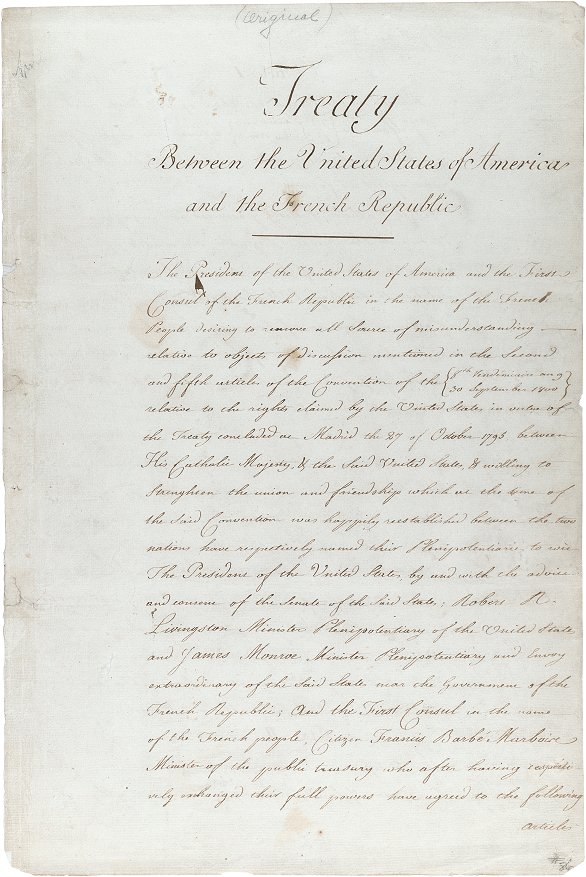

The result? An unexpected 180° turn by the formerly coy French Minister of the Treasury, who offered to sell not just New Orleans, but the entire Louisiana Territory, to the United States for $15,000,000 in funds France could use to fuel Napoleon’s other ambitions—including war with Britain.

The rest, as they say, was paperwork. The treaty was signed by Robert Livingston, James Monroe, and François Barbé-Marbois at the Hôtel Tubeuf in Paris on April 30, 1803.

It was announced by Thomas Jefferson to the American people on July 4 and was finally ratified by the Senate with a vote of twenty four to seven on October 20.

Interestingly, it was a British bank—Baring & Co. Bank—that financed the deal, providing the cash to Napoleon and then selling the Territory back to the United States in exchange for bonds with 6 percent interest attached.

Overall, the total cost to the young states was $27 million, but no one could deny that Jefferson had managed to buy Louisiana “for a song,” as General Horatio Gates said.

The Complex Legacy of the Louisiana Purchase

While it’s often portrayed as the ultimate bargain for a young nation-in-the-making, the Louisiana Purchase did much more than simply double the size of the country and affirm the United States’ role as a growing world power.

Like so many events in American history, the Purchase left in its wake a complex set of powerful, sweeping changes that affected the lives of countless generations for both good and ill.

- In addition to stepping beyond powers named in the Constitution as explicitly held by the President (and that action’s approval by the Senate), Jefferson’s move to buy the land effectively opened up the western half of North America to exploration, exploitation, and settlement. The Western expansionism, Manifest Destiny, and the eventual conquest of the rest of the lands now held by the United States, all had their birth in the Purchase.

- Modern democracy, free-market capitalism, and the decidedly American approach of spreading both as far and wide as possible, were all secondary effects of the westward expansion fed by the Purchase. They continue to drive our evolving global economy and business climate today.

- Tellingly, the Louisiana Purchase did not factor rights and protections for indigenous peoples already present on the land being bickered over by the United States and European powers. While some native peoples were ostensibly compensated for the land so seized, even the paltry sum paid to France can seem a king’s ransom compared to the relative pittance doled out to the indigenous peoples who were often forcibly relocated as the United States’ relentless expansion continued.

A Purchase That Changed the World

Whether you’re restocking the copier room or snatching up half a billion acres of land for your growing country, procurement gives you a chance to seek not just savings, but value.

Take the time to understand your own goals and the goals of those with whom you negotiate, be on the lookout for opportunities to leverage changing circumstances, and don’t be afraid to think outside the trillion-dollar box, and you might just strike a deal that creates Louisiana-sized value for your business.